"I'm interested in the link between architecture and politics." What did Dominik Nosko gain from the Climate Academy organised by Zuzana Čaputová?

8/3/2024

You participated in the Climate Academy in Bratislava during last summer together with other selected students. I saw a photo with the Slovak President, what was it all about?

Zuzana Čaputová has always been interested in protecting the environment, so she tries to keep bringing up the topic, even though presidential powers in this area are limited. That is why she has decided to bring together a community of young people every year through the Climate Academy. I took part in the second year, and 25 Slovak students were selected. Some of them study at home, and there were other students with me from the Czech Republic, but also from French, Dutch, Danish schools and the United States. We represented a wide range of disciplines, from people working directly on climate change to those studying international relations and political science, or those studying literature and technology. The program, too, was built to cover as broad a range of complex issues as possible.

What activities have been prepared for you?

The Academy took a week and started with a reception with the President, when we had the opportunity to have our first informal discussion with her. We discussed how to argue and counter hoaxes properly with representatives of the Slovak Debating Association. Jakub Filo, a journalist from the SME newspaper who covers climate change, gave us an insight into the role of the media on this issue and why this topic is still in the background in some Slovak media. It also included data and scientific facts. With Juraj Zamkovský from the Slovak Innovation and Energy Agency we discussed the topic of de-growth, the fact that a steady growth of material and energy consumption is neither possible nor sustainable in the long term. He also presented interesting data that, for example, in the least developed districts of Slovakia, such as Rimavská Sobota, energy savings in buildings by transforming them can reach up to 70%. This illustrates how important the work of architects will be in the renovation and development of small regions.

What was the most interesting part?

Leaving aside the opportunity to meet and talk with Zuzana Čaputová and the urban topics that are naturally linked to my studies, I think the most valuable part for me was the part based on hard data and its impacts. While I am not completely lost in this area, I have not had the opportunity to get to know some of the facts presented in such detail until now. And also the discussion with young people from different fields on a topic that is common to us was very enriching.

Why did you attend the Climate Academy? Or perhaps: What did you say to Zuzana Čaputová when she asked you this question on the first day?

I said that as an architecture student, I feel that some of the public perceives our field as pretty pictures, but there are other questions to be answered behind quality visuals, including the fact that architecture and the creation of urban environments have an impact on sustainability and society.

Zuzana Čaputová introduced the Presidential Green Seal, an award for the renovation of public buildings in Slovakia. It is not only environmental aspects that are evaluated, but also aesthetics and architectural quality. The evaluation criteria were established in cooperation with the Slovak Chamber of Architects, the Slovak Green Building Council and the Institute of Circular Economy.

The Presidential Green Seal offers a more comprehensive perspective than some commercial certificates?

LEED or Breeam certificates only assess environmental parameters and aesthetic, form or impact on society are not represented. Whereas the President's Office's initiative emphasizes aesthetic qualities, the application of art in the building, and positive impact on the community. The first green seal was awarded to the Emil Belluš Secondary School of Industry in Trenčín.

Is sustainability of architecture a long-term theme for you?

I think it developed gradually, also based on the activities I did outside my studies. And I don't just mean environmental sustainability, but also social sustainability. I always try to look for something more, to find architecture beyond floor plans, sections and visualizations. Thinking about how far the role of the architect goes, where it overlaps with other professions but also where it should no longer interfere. I am interested in the political level of architecture, to what extent our profession has a political, activist and social role.

This is probably often quite unrewarding. Parking and the use of space by cars influences elections in most Czech cities. The 15-minute city has become a controversial issue in Britain. The original idea of making as many services as possible available close to home has sparked protests from groups who fear the government will use the concept to restrict free movement. Shall I ask for any positive examples?

City officials can have a much greater influence on the creation of urban planning than architects, individuals who have undergone professional studies and understand the issues. In some places these professions are intertwined, and Bratislava has been led for the second term by an architect and a mayor in one person. I don't live there and I come from a different part of Slovakia, but as an observer it seems to me that the major steps in the creation of the city started to take place there after he arrived. Whether it is the quality of the revitalization of public spaces or the setting of stricter rules in the permitting process for large development projects.

Let's get into the New European Bauhaus, it's also about connecting politics and architecture. You are involved in organizing workshops under the CrAFt brand.

The CrAFt (Creating Actionable Futures) project is one of the initiatives of the New European Bauhaus. Its aim is to connect municipalities and public policy makers with students from the academic and artistic spheres. Our main goal is to organise workshops, for which we have set the topics ourselves. We completely prepare the events with other students, find and invite speakers.

One workshop has already taken place at Manchester School of Art and we are planning another in Amsterdam. The Manchester workshop focused on how a university environment, which is primarily made up of young people, could reduce the generation gap in public space. The preparatory group includes 8 students from Prague, Amsterdam, Bologna and Trondheim. There are students who work in graphic or textile design, and computer science is also represented.

Who are your speakers?

We try to invite local experts from different fields. We have arranged for various stakeholders to give talks in Manchester. Eunice Bélidor, curator, writer and researcher, gave a talk on linking writing with race issues and feminism. Or architect Dan Dubowitz, who focuses on collaborative urbanism. We are preparing a series of reports from the workshops that can be used further if someone wants to repeat our workshop.

How does it feel to be on the side of a teacher, someone who is trying to get others to take action and get them thinking?

It's an interesting position, it trains you to be prepared but also to improvise. Another challenge is that you are co-organizing something in a place you have never been before and you are only in online communication with people you have never met in person. Only the workshop will show if everything was well prepared.

The aim of CrAFt is for students to experience professional level organising, communication with professionals from different sectors and the overall functioning of a European project. As an architecture student, I hadn't encountered much of the bureaucratic or formal rules that such projects are subject to, so this was also a new experience for me.

Will the Amsterdam workshop be different?

The theme is "re-growing the city" and will focus on urban gardens. We are collaborating with Gerrit Rietveld Academie, which is an art school in Amsterdam. It includes what is called The Garden Department and they will be hosting the workshop. It's a group of students who started an informal garden at the academy in 2019 and they are trying to make it part of the school's curriculum as a link between the garden and the artistic professions. We will be producing a diary of feelings, texts and collages from a specific place in Amsterdam that we hope to change. The question will be how to implement elements from urban gardens more into public spaces.

The basic goals of the New European Bauhaus can perhaps be summarised briefly as "that science, art, architecture and design can help us in many ways (towards sustainability)". Yet I find it difficult to navigate the project launched by the European Commission. If students would like to get involved in some of the activities, where would you recommend starting?

Perhaps the problem with the New European Bauhaus is that it is very complex. I would therefore understand it as a label that covers a number of smaller initiatives that aim to politically grasp the issue of green transformation, to materialize the Green Deal into concrete projects and activities. The very reuse of the word Bauhaus is meant to refer to the post-crisis era in which the original Bauhaus as an architectural movement emerged, and in which we find ourselves now. The original one combined, among other things, architecture, design and art. The new one, the European one, aims to combine science, culture, art and politics.

I think the New European Bauhaus Prize may be of interest to students of architecture, landscape architecture and design. The competition can be for a completed project that has already had a real impact, but also for a proposal to revitalise an area or a design concept. I know that in previous years projects from architecture schools have won or been among the finalists. The winners get funding and connections with stakeholders to further develop their concept.

Of course, it is also possible to join the CrAFt project, of which I myself am a part. It accepts new students every six months based on a CV, a cover letter and previous activities.

Can you introduce me to your bachelor's project? Are you now at the normal stage where the original beautiful concept of the research is crumbling under the reality of building regulations?

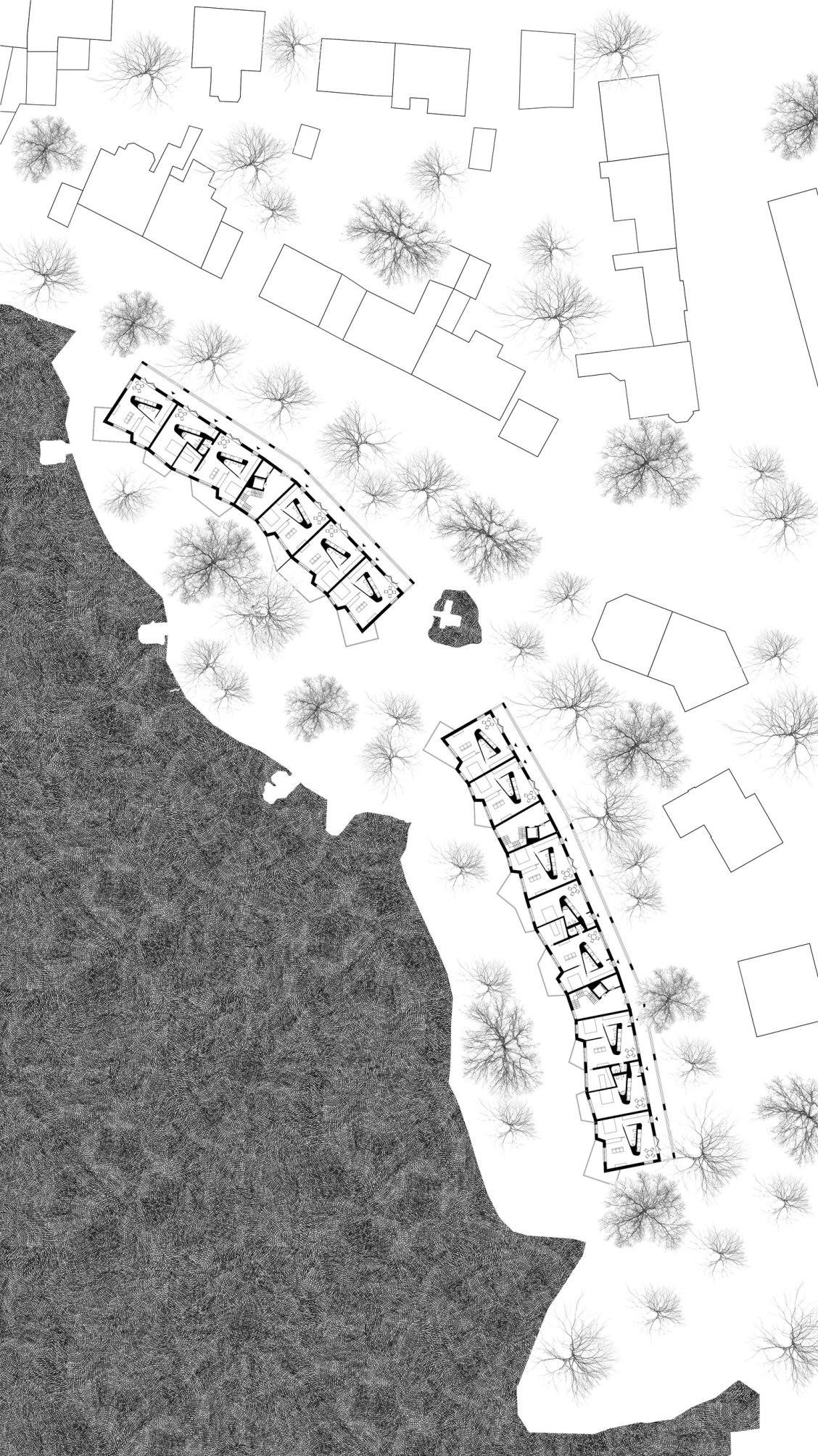

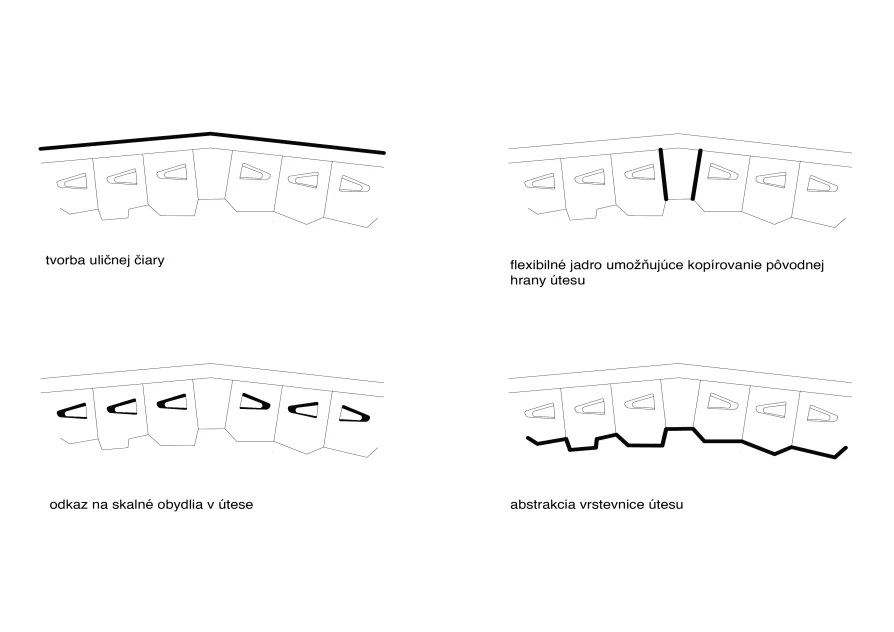

I am working on it in the Zmek-Krýzl-Novotný studio, where we focused on the Petřiny housing estate. The studio offers a free approach to the topic, which can be challenging in the case of a bachelor's project. You have to find your own assignment, location and typology, but this gives you great freedom to explore new themes and approaches. After various trial and error, I tried to base the project on something theoretical. From historical analyses and visits to archives, I discovered that in the 1920s and 1930s, emergency colonies began to form below Petřiny for residents who could not afford to live in Prague and moved to its outskirts. Mostly these were wooden buildings that were built illegally, but the northern edge of Petřiny is formed by a sandstone quarry that was created by mining around 1915, part of which also began to form rock dwellings. The caves are still there and I was able to look into them. My undergraduate project focused on social housing as a response to the context of the place. The new houses follow the original edge of the quarry, which has disappeared due to sandstone extraction.

It was interesting to observe the parallels with the unaffordability of housing, which is still an issue in Prague today, and how the failure to address this issue then led to the creation of excluded communities.

You were in Winy Maas' studio for a semester. Did you like the approach of The Why Factory?

I think there's a lot of conflicting opinions about the studio at the school. Some of The Why Factory's process I appreciated, some of the stuff I was critical of. But the positive experience was working in a large group on one topic all semester. The ability to agree, to seek compromise, but also to detach from individual authorship of the project. The theoretical foundation of the project works well. Emphasis was placed on making analytical data processing part of the work and, more importantly, getting it right. It was not just student conjecture, the analysis was conducted according to academic standards, and the conclusions we drew under the supervision of the faculty were not arbitrary or self-serving.

Projects can also be based on a feeling and a quick sketch.

I think architecture should also be an emotional and poetic thing. The extent to which design should be influenced by emotion will probably always be individual. But there are situations where it is necessary to add to the feelings with well-founded conclusions.

The interview was led by Pavel Fuchs.