The lecture focuses on detailed information about the demanding and award-winning restoration of Baroque gardens, which are among the key monuments of Baroque garden design in this country.

20/2/2023

Photo: Petr Špánek

Děčín Castle is waking up after years of devastation. But the successful repair of the gloriette is not your first project in the premises?

The town of Děčín took the devastated castle on its responsibility after the Soviet army and began to look for new uses. During my studies at the Faculty of Architecture, I devoted some of my seminar papers to the castle grounds and the surrounding gardens. With my future wife I went through the ruined rooms of the west wing of the castle. We documented ceiling fabions or damaged floors and explored the main tower. And when the west wing of the castle was completed according to the project of the architect Vlastimil Stránský from Děčín, we were the first to have a wedding in the main hall. So I have many personal experiences and memories connected with the complex. After school, I also had the opportunity to work on the grounds, especially during the revitalization of the southern chateau gardens.

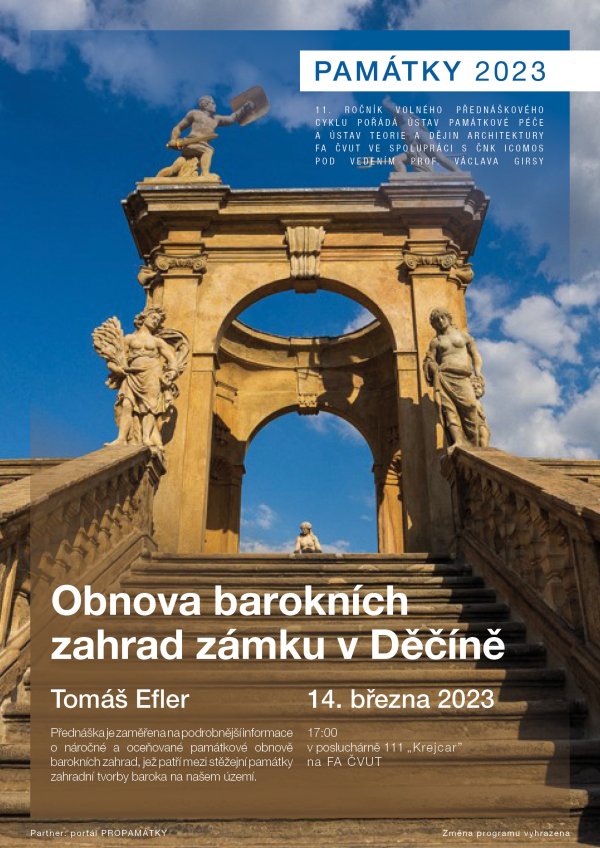

From a distance, the gloriette itself looks like an inconspicuous little building. However, it is a multi-storey house with a number of staircases and other spaces.

It is an attractive Baroque building that offers a view of the Elbe Canyon. It stands on a rock massif and it is very likely that there was a defensive tower here in the times when the castle of Děčín was still a medieval castle. During the restoration we even discovered that there are inaccessible cellars under the gloriette.

The gloriette is located in the Rose Garden next to the Long Ride, which is the dominant driveway to the castle lined with high walls with arcades. The garden was called the Lodge Garden in the Baroque era, but was only renamed during the 19th century, thanks to its renowned rose cultivation. The gloriette forms the culmination of the garden's composition, where the nobility could climb up several stone staircases with balustrades.

Before your intervention, the renovations were relatively recent. Why weren't they completely successful?

Gloriet is inspired by the architecture of the Mediterranean, but in our conditions such a fragile building is inherently difficult. There have been various remediations of dampness and other technical problems. However, they did not focus on architectural rehabilitation and the technical solutions were not chosen appropriately either. Thus, the gloriette has been insensitively rehabilitated in the past with a series of cement sprayings and rehabilitation plasters. Not only in the walls, but in the entire rock mass, moisture was retained. We have therefore had to repeatedly apply so-called sacrificial plasters, which draw out some of the salts and then remove them. However, the process of drying out the building will take some time.

How does the restoration of a Baroque monument begin?

Quality documentation and pre-project and project preparation are essential, which the studio under the leadership of Professor Václav Girsa has always emphasized. The actual implementation began with the uncovering of modern masonry, plaster and other inappropriate remediation measures. We had to verify the actual state of the damage in order to consider the expected course of action.

In the lower part of the gloriette we planned to reopen the bricked-up arcades, but we had to proceed with caution. We didn't know if their later brickwork had solved some static problem. It was confirmed that they were just thin partitions with no contact with the historic structures. So we could have easily missed them. In addition, after the removal of the walling, we found the original lime plaster and paintwork hidden, which we could use as a model to prepare for the restoration of the plaster and paint. Often important details that have disappeared elsewhere can be preserved in the walling.

Photo: Petr Špánek

Even when a monument is repaired, the building's appearance often changes. Were you looking for an older form of gloriette that you wanted to return to?

The facades of the gloriette were always whitewashed during the last renovation works. However, the plaster has mostly cracked, fallen off and the facade has been damaged by flooding and blooming salts. We went back to the ochre sand colour. The decision also fits in with the concept of the whole area. In addition, we restored the lysens and other architectural features such as the window framing that had gradually disappeared during previous repairs to the gloriette.

we have found and historical photodocumentation from the archival collections in Děčín. Interestingly, the gloriette was partially overshadowed by the development of town houses in Křížová Street below the castle. Unfortunately, they were demolished in the 1960s. The pavilion suddenly appeared as a dominant feature of the public space in front of the Church of the Holy Cross, now a popular pedestrian area. The current presentation of the gloriette is therefore not an exact return to its historical form in a specific time period, but a contemporary artistic presentation of historic architecture with detailed respect for both the original Baroque composition and its partial changes throughout history, with subtle contemporary adjustments to the details.

You even discovered a former water pool under the pavement. I guess it was never easy to get water on the castle rock?

Water features are documented in old descriptions. The fountains can be seen in historical drawings and engravings and they are also documented by our archaeological discoveries. Next to or inside Salla Terena there was supposed to be a statue of Poseidon and from its fountain flowed a spring of water that fed other fountains in the garden. Catfish were also said to have been kept in the pool that dominated the lower terrace in front of the gloriette. Similar bizarre descriptions are known from Italian Baroque gardens, and it is certain that the decoration and water system in the gardens of the castle in Děčín was also very remarkable. The water was supposedly brought to the castle rock by a long-distance water pipeline and probably also pumped from under the castle.

Photo: Petr Špánek

Does anyone have the desire to put water back in the gardens?

Yes, this is foreseen in the next phases. However, it will definitely not be a return to the demanding baroque form of the water regime, including the waterfalls. However, in some semblance, the water features will hopefully be restored and the forthcoming project to restore the Rose Garden itself includes this.

But you used the pool to drain the gloriette.

The architect Studničný, who saved historical monuments in Děčín in the 1950s and 1960s, created a paved area in front of the gloriette and cancelled the previous floral arrangement that had been on the site of the baroque pool. We proposed a new blending of multiple historical layers.

We have left a well-maintained paved area around the perimeter. But at the same time, we have restored the central part, where the flower bed symbolises the former swimming pool. The water from the staircase and the terrace flows into the central part, under which we have created a drainage system. As a result, rainwater is gradually absorbed by the greenery and does not run off the gloriette quickly into the sewer. In the future, a drinking fountain will be built here.

In the Baroque period, water probably flowed from the Sala Terrena through the entire garden into this Baroque pool and finally into the water basin carved out of the rock massif below the gloriette. A spillway allowed the waterfall to be released towards Cross Street. The stone gargoyle has been restored and on important occasions in the future it will be possible to fill the reservoir and lower the small waterfall. But we did not dare, because of the threat to the stability of the whole rock, to bring all the rainwater under the gloriette, as it worked during the Baroque period.

Photo: Petr Špánek

You even had to disassemble and move part of the gloriette?

A significant part of the building is made of beautifully processed stones. The top of the observation pavilion is not fully roofed, but opens in the middle of a massive profiled cornice through a circular opening with a view to the sky. Unfortunately, it is some of the sandstone blocks from the top of the pavilion that have been badly cracked. We knew that we were not just in for some simple surface treatment, but that we really needed to address this part more fundamentally.

The entire top of the gloriette was disassembled so that we could inspect the other layers. Modern technology was also used, one of the largest cranes came to Dlouhá jízda, the stonemasons managed to loosen and then attach the individual pieces to the rope. These were moved to the terrace of the Rose Garden where restoration, treatment and conservation took place. Once the crown section of the pavilion was repaired, the cornice elements flew back and were carefully set back into their original position.

We have added a new lead sheet cover to the top of the pavilion, which should extend the life of the restoration of this part of the gloriette. However, the lead sheet is as little visible as possible. This is because prominent cladding is a common nuisance on some monuments.

Photo: Petr Špánek

You worked with dozens of other professions during the renovation. Students, who are used mainly to classical architectural projects, are interested in the role of the architect in this type of project.

Even when building a new apartment or house, you work with a lot of people. When renovating a historic building, the role of the architect may not be so visible at first glance. You are not creating something completely new that grows under your hands, but you have the privilege of participating in the restoration of the work of your predecessors.

The architect, together with the technical supervisor, has a responsible role to manage the restoration so that it is actually carried out as gently as possible, so that the individual professions do not spoil each other's work, so that things fit together. You have to meet the often different requirements - between the investor, the technical parameters and the conservation authority. Many details are discussed, you commission special expertise for certain parts. The solution is not always clear-cut, you work with atypical situations without catalogue solutions, creativity and improvisation are often necessary. The omnipresent atypicality, individuality and craftsmanship in the restoration of historical monuments is probably the biggest difference in architectural work compared to the mainstream building technical trends of industrialization, typification and robotization in construction.

What were the biggest discussions about?

The question is always the degree of cleaning of the elements, which you can observe in the repair of all stone monuments. You will find examples where the building is almost left as a ruin, with only basic conservation. Some reconstructions, on the other hand, shine with newness after restoration and look as if the Baroque builders had left them yesterday.

We have chosen a middle way, so it is in a way an individual interpretation and presentation. Gloriette has had a number of finishes in the past, so it would be possible to give all the stonework a subtle coat of colour to make it more colour-coordinated with the facades. This would have been a big shock to many people, with some conservationists cheering and others tearing their hair out. However, the fact that beautiful sandstone stones were used to build the gloriette, with different coloured marbling and stone colouring, also played a role.

That is why we did not use more drastic forms, so as not to damage the surface layer of the stone completely. Occasionally, especially in the folds, remnants of older paint or dirt remained. The architect's creativity can therefore often be hidden in the various material or technical nuances of the solution in close collaboration with erudite restorers and specialised craftsmen.

Photo: Petr Špánek

As far as I know, the gloriette is not the only prospect you have dealt with in Děčín?

We also dealt with the restoration of the Labská stráž lookout, much younger than the gloriette, from the end of the nineteenth century. It is located on the nearby Stoličná hora in the Kvádrberk forest park, away from the urban development. It is a stone gazebo made up of four pillars, topped with a concrete dome. The site has been devastated and abandoned for a long time. We also found bullet marks, supposedly from the end of the Second World War. With the funds of the city of Děčín and the contribution of the Ústí Region, the pavilion was repaired and at the same time the traces of its age were preserved. It is a very popular sightseeing spot.

Planning the construction and transporting materials and craftsmen there must have been even more complicated than on the gloriette.

Yes, it must have been an agony for the company. They drove up in a jeep and had a warehouse at a distant petrol station from where they had to carry water. The process of repair was not ideal because the lookout was not yet a declared cultural monument at that time and was not subject to some of the restoration requirements that it deserved and we tried to enforce them anyway. However, this is again a question of the criteria of the selection procedures and the setting of qualifications in the restoration process.

Photo: Petr Špánek

What projects are currently waiting for you?

I mostly work on rural estates in North Bohemia. Thanks to my past realizations, I get commissions related to abandoned monuments. Due to their technical condition, they require mainly the determination and willingness of the owners to embark on a demanding restoration. Today's planners often recommend the owners to demolish such a house. Also, craftsmen do not want to bother with an old building and rescue it in a complicated way when they can do at least three other simpler buildings in the same time. The current energy situation is not helping either.

Photo: Petr Pivoňka

Let's end the conversation on a positive note. Your students turned in their semester projects in the studio, what topics did you work on together?

I run a vernacular studio at the Faculty of Architecture of the CTU. I am also working on traditional local architecture in various predominantly Czech regions. This time we went to Mnichovo Hradiště, not far from Mladá Boleslav. We dealt with sites right in the centre of the town, especially around the rectory. Some of the students dealt with the village of Loukov, which is a rural conservation area on the banks of the Jizera River in an elevated position with a beautiful church and a number of rural farmsteads. Here, too, there is a ruined abandoned rectory with a barn and farm facilities.

The focus was on these two church grounds, their revitalization and the search for a new use not only for the parish community. In addition, we were also interested in the nearby Bažantnice Chateau near Loukov, which is currently undergoing a phased renovation by its enthusiastic owner, my colleague Tomáš Tomsa.

Students have the opportunity to work on specific assignments in which they focus on the restoration of historic buildings and new buildings in close proximity to cultural monuments.

We select sites that are strongly shaped by the past, such as conservation areas or old industrial sites. The architectural design has to deal with the whole context. We are looking for more sensitive solutions with the students, which do not create a contrast or a distinctive intervention, but develop and re-emphasise the hidden qualities of the whole environment.

Already have an idea where you'll be directing your attention next semester?

We return to Žatecko periodically. Its hop-growing landscape, hopefully, is heading towards being inscribed on the UNESCO list. Students have the opportunity to choose between the site of the Prague suburb directly in Žatec and the hop-growing village of Bezděkov, and to experience, among other things, the conversion and revitalisation of historic industrial sites associated with a rich cultural tradition of hop growing and trade.

The interview was led by Pavel Fuchs.

Photo: Dagmar Hujerová

For the content of this site is responsible: Ing. arch. Kateřina Rottová, Ph.D.